Sprott Radio Podcast

Energy Humanism

While climate change dominates the headlines, Robert Bryce passionately suggests the plight of billions of people living without access to energy should also be front and center. He joins host Ed Coyne to make the case for abundant, affordable energy for all, or what he calls Energy Humanism.

Podcast Transcript

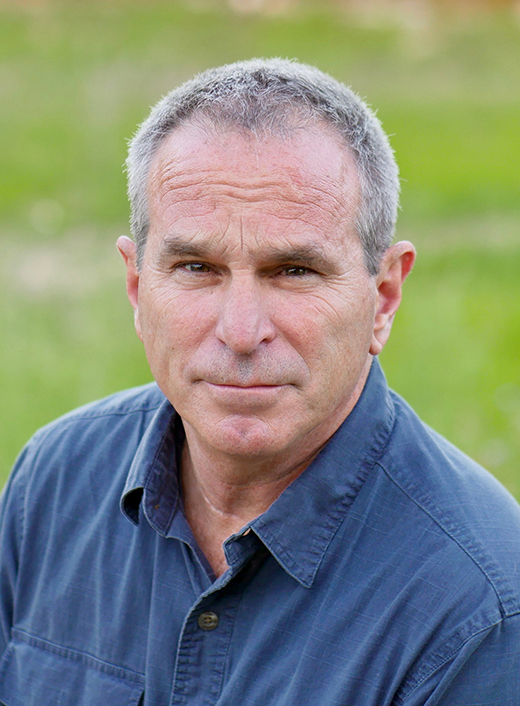

Ed Coyne: Hello and welcome to Sprott Radio. I'm your host, Ed Coyne, Senior Managing Partner at Sprott Asset Management. I'm pleased to welcome a new guest to our podcast, Robert Bryce, an established public speaker, author, and podcaster on all things energy. Robert, thank you for joining me today on Sprott Radio.

Robert Bryce: Happy to be with you, Ed.

Ed Coyne: Robert, let's start with your work and background and some of the books you've done—specifically, the most recent one, A Question of Power. Talk a bit about that. What were some of the points of that book?

Robert Bryce: Sure. My predilection when I introduced myself is, yes, I do all that other stuff. I'm a reporter and journalist. I've been married to the same woman and loved this woman for 38 years. Lorin and I have been married all this time. We've got three great kids, so my life's priority is family. I always make sure to give them a shout-out. I work because I love what I do, and it also helps put food on the table to make the family thing work.

I've written six books. Believe it or not, my first book was on Enron, published 23 years ago. I wrote that book in six months. It's called Pipe Dreams: Greed, Ego, and the Death of Enron. Here we are all these years later, and Enron still haunts power markets here in the U.S. and around the world because of their view that electricity is a commodity when, in fact, it's a service.

That misapprehension of what electricity is and how the electricity business works, I think, has been something that's still problematic, which we'll dive into. My latest book, published five years ago, is A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations, which I think is still fresh today. The themes haven't changed. What's the difference between the rich countries and the poor countries? There are many reasons, but it's the availability of cheap, abundant, reliable power.

I've also done two documentaries in 2019 with my colleague, Tyson Culver. We released Juice: How Electricity Explains the World, and then a year ago, we released a five-part docuseries called Juice: Power, Politics & The Grid. That's a five-part docuseries. It's available at juicetheseries.com, and the movie is juicethemovie.com. I've been incredibly fortunate in my career to do what I do. I love writing about energy and power.

The energy sector is the world's biggest and most important business; every other business depends on it. I'm incredibly fortunate to do what I do. One of the great things is that I'm always learning because the business is so big and complex and touches everything else. Now, of course, things are even more exciting as we have a new president here in the U.S. who's just shaking things up like a snowball. What do you call those?

Ed Coyne: Snow globe.

Robert Bryce: Snow globe. It's just like you mentioned, all these executive orders. It's the biggest turnaround in American energy politics in modern American history. It's incredible what has already happened just in one day.

Ed Coyne: Let's stay on that for a second. I have it as a later question, but let's dive right into that. Who will some winners and losers potentially be in the next four years? What's your thought on that?

Robert Bryce: Off the bat, one of the things that I'm most encouraged about with Trump is his appointment of Chris Wright as secretary of energy. Chris is the first energy executive to become an energy secretary. That by itself is amazing. Ronald Reagan appointed a dentist to the energy secretary job. We've had lawyers. We've had all these Harvard guys and technocrats. Now, we have someone who knows the energy business and Chris, in particular, understands nuclear.

He is passionate about energy. I consider him a friend of mine. He's incredibly smart, innovative and entrepreneurial. Having him in that job is fantastic because he's an energy realist and an energy humanist, and those go together. What do I hope the Trump administration can do, among other things?

Well, one, I think, is to restore the humanist aspect to this discussion about energy, and I think Chris will do that. I think they have the potential to catalyze real forward momentum on the nuclear side, both in terms of regulation, nuclear fuel, fabrication, and uranium mining. That was the mining issue. Uranium was mentioned in his executive orders on his first day in office. I'm very hopeful for that. It is the biggest change and reversal in modern history regarding energy policy in America and could have a major impact across many sectors.

Ed Coyne: I think it's interesting you just brought up nuclear because, during the campaign, everyone just assumed the whole "drill, baby, drill" quote was all oil and gas and nothing else. Surprisingly to people, he's open to everything and understands that we need everything. Let's review some of the “everythings” out there. We obviously have oil and gas. You mentioned nuclear. There's battery technology, solar and wind. I'd love to hear your thoughts on each one of those sources of energy.

Robert Bryce: Let's start with coal because it's so unfashionable, and I understand why. From where I sit, the U.S. should not be closing more coal plants. We need to maintain fuel diversity in our power sector. I'm pro-natural gas, but I fear we're becoming too dependent on gas as a power-generation fuel. We're now at a record high. I think 44% or 45%. I need to look at that number regarding the percentage of gas and the overall electricity mix in the U.S.

In most times, that's fine. Not a problem. During extreme weather events like extreme cold, the availability of gas, which is just-in-time, is a problem. I'm going back to coal briefly. Many coal plants slated for closure will stay open longer because of growing power demand in the U.S. Coal ain't going away. Particularly, it's not going away in China and India.

I've written about this extensively in the U.S. and Western Europe; they've got this idea, "Oh, if we quit coal, the rest of the world is going to do so as well," it's just flat wrong. If you look at the amount of coal capacity that's being built in China today, being built, not discussed, not on blueprints, not in the discussion-permitting phase, actually under construction, it's roughly equal to the entire installed base of the coal fleet in the U.S., about 190 gigawatts.

By the time China builds out that capacity, the coal-fired capacity in China will be equal to the entire capacity of the U.S. grid, about 1.3 terawatts. Let's not kid ourselves about what is happening with CO2 and the reality of the challenge of CO2 emissions around the world. That's coal. I'm bullish on gas—gas demand is growing and will continue to grow. Does that mean the price will go up? Hell, if I know. You know what I mean?

Who knows what will happen with the price? Demand for gas will continue rising for many reasons. U.S. LNG (liquified natural gas) exports will increase now. Trump will remove the pause put in place by the Biden crowd, which was just a big mistake. I'm very bullish on natural gas. I've said the same thing for 15 years: end-to-end natural gas to nuclear. This is the way forward.

Oil as well. If oil didn't exist, we'd have to invent it. It's a miracle substance. It's not going away. The installed base of motor vehicles and transportation machinery that uses oil, whether diesel, jet, or bunker, is irreplaceable. The world economy runs on oil, period—end of sentence. Elvis left the building. Oil's going to stick around. Then, a lot of things are in the mix, whether it's hydro, which won't increase much anywhere around the world because we've built effectively all the dams we're going to build.

We're taking dams down. We're not building many more, except maybe in China or Africa. Then, you have biomass, solar, and wind. There's the rest of it. It's all fine. Solar and wind only play a part in the electricity sector. They're not going to touch transportation. They're not going to play a huge role in industry. I think the main problem with wind and solar energy, in addition to intermittency, is land use, which is forcing those conflicts worldwide. I've documented them in the renewable rejection database.

Ed Coyne: You started by talking about fuel diversity. I think that's such an important topic for people to understand because I think early on when wind, solar, and now even nuclear, people are starting to embrace nuclear again and understanding we have to have a baseload 24/7 power source that potentially is more sustainable and cleaner and so forth. That diversity thing, I think, is so important because initially, people thought it was one versus the other. It's either oil and gas, or it's wind and solar. It's either clean and sustainable, or it's dirty and polluting. Can you talk about that diversity and why it is so important?

Robert Bryce: The classic way to reply to this, of course, is to quote Churchill. In 1906, Churchill was the lord of the admiralty or whatever the fancy British title was. Remember when the Brits converted their warships from coal to oil? He said, "Safety and certainty in oil lie in variety and variety alone." What he was saying was energy security. He's talking about oil, but the security of that supply is in variety and variety alone. It just makes sense.

If you have a civilization as big as ours, regardless of whether you're in the U.S. or Canada or Mexico, any industrialized or modern country, you risk the collapse of civilization if you have a system that's too reliant on one thing. That's particularly true when it comes to electricity. You have to recognize where your risks are. Regarding the electric grid, I'm adamantly favor having a diverse set of fuels. Coal isn't fashionable, but that's fine. I get it.

There are four people and five elk who live in Wyoming. There's nobody there. You can build coal plants in Wyoming. It's going to be fine. It's not going to decide the planet's future if you burn coal in Wyoming atop the Powder River Basin, which is the largest deposit of coal in the world. The U.S. has more coal resources than any other country in the world. We're not the Saudi Arabia of coal. We're the entire OPEC of coal, yet we won't burn it? We need that security.

If we talk realistically about where we are and where we're going, I'm pro-natural gas and pro-coal. Still, we need nuclear, not necessarily just for the CO2 issues but for the fuel and energy security attributes it brings to the grid. Having on-site fuel storage, a small footprint, and sparing land for nature are all reasons to be pro-nuclear, and they don't have anything to do with carbon.

Ed Coyne: Yes, I think that the land and nature aspect with small modular [reactors] (or SMRs) and even microreactors becoming a more household term, I think you're going to see that become surprisingly one of the most environmental-friendly types of solutions out there, which wasn't that long ago that it was the opposite of that from a narrative standpoint.

Robert Bryce: I'm pro-nuclear. I've said the same thing. If you're anti-carbon dioxide and anti-nuclear, you're pro-blackout. Well, I'm anti-blackout. I'm adamantly anti-blackout. We look at the nuclear sector now. I'm jumping ahead, maybe on your list of questions, but will it be big reactors? Is it going to be small reactors? I wrote a piece recently on seven reasons to be skeptical about SMRs. I just walked through what these issues are. The cost of the reactors is still high.

We still haven't seen them proven in the commercial market. I wrote about NuScale Power 16 years ago. They still haven't built a reactor. It took them six years and $500 million to get a permit from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The cost of capital, fuel, regulation, security—all of these things are obstacles for SMRs, just as they are for gigawatt-scale reactors. I'm pro-nuclear, but I'm also very sober about where we are and where we're going. We need that sobriety when we talk about what's coming up and which reactor designs are going to be the ones that succeed in the commercial market.

Ed Coyne: Let's talk about the storage of energy then.

Robert Bryce: Sure.

Ed Coyne: A lot was made of battery technology, predominantly in the electric car world. Now that it's expanded and saying, "Okay, can we live in a world where we can create tons of energy through solar or wind or hydro or oil and gas and then store that energy into a large battery technology and move that energy around to places that need it?" Is that pie in the sky? Is that something you see potentially happening? What's your view on the storage of created energy versus just-in-time energy?

Robert Bryce: That's an interesting way to think about it because you phrased it when I thought, "Okay. Well, what about the storage of energy that's in the gas tank in my truck?" That is a wonderful storage mechanism: gasoline has a very high energy density, is stable at standard temperature and pressure, is easy to handle and move, is relatively light at seven pounds a gallon, and has this energy density that is hard to match with anything.

You can compare that with the best lithium-ion batteries, even if you assume they're five, six-fold better in terms of energy conversion; they're still 120 at the energy density of gasoline. I'll say it very bluntly. Batteries are getting better. It's true, but batteries still suck. They sucked in Edison's day. They suck now. You can't charge them too fast. You can't charge them too slowly. It's like Goldilocks. They have to be just right.

Then, look at what we've seen in Moss Landing at the Vistra battery facility. There, it caught fire again. They had a massive fire at that battery storage facility. Was it 18 months ago, something like that? The fire raged for days. They kept a fire engine on-site there, Ed, for a month because they were afraid that the thing would catch fire again. Well, guess what? They didn't keep the engine there long enough because it caught fire again. We've talked about land use.

One of the other emerging issues around batteries is that, now, you're seeing more communities saying, "Oh, we saw that battery fire. We don't want those batteries here." I think it was in October. Escondido, California, passed a measure. They had a temporary moratorium on any new battery storage within the city limits. If these lithium-ion batteries catch fire, you must stand back and get the hot dogs out because you can't put them out. They'll burn themselves out because they create their own fuel and their oxygen.

Ed Coyne: What does all this mean for the rest of the world as it relates to not having energy and maybe getting it for the first time? What will that look like in the long term in your mind?

Robert Bryce: This an important question that you're asking, Ed. It's one that's very dear to me and dear to my heart. It goes back to this idea about energy humanism and energy realism. We have this Western-centric conceit about the importance of the U.S., Western Europe, or Canada: "Oh, we're going to decarbonize and, therefore, this is going to solve the problem."

We have all these people who fashion themselves—climate champions, warriors, hawks, etc. Roughly three billion people live in places where, on average, their electricity consumption is less than 1,200 kilowatt-hours per capita per year, which means their electricity use is about equal to that of an average kitchen refrigerator in the United States.

Ed Coyne: Wow.

Robert Bryce: We live in a world where energy poverty is rampant. Two billion people cook food in their homes with dung, wood, wheat straw, and biomass. Two billion. Not my numbers, the World Health Organization numbers. There are a couple of other quick numbers here to put this into perspective. Why do we care? Well, if we're humanists, we should care. Why? Because two billion people cook their food by open flame.

Every year, again, according to the World Health Organization, over three million people die from indoor air pollution caused by those lousy cooking fuels. Three million. To put that in perspective, more people die. It's primarily women and girls who are dying every year from indoor air pollution caused by lousy cooking fuels than die every year from AIDS, HIV, cholera, malaria, and tuberculosis combined. This is a public health crisis, Ed Coyne. It's a public health crisis.

What about these people who are dying for lack of even a bit of propane? It's just this conceit and this utter disregard for the human issues here. To me, it's inexcusable. It's something that sets me a flame because-- I did say "sets me a flame," didn't I?

Ed Coyne: You did.

Robert Bryce: It hypes me up. As my late brother John Bryce said, "Grills my cheese."

Where are the humanists when it comes to these issues? Yes, CO2. Yes, climate change. Okay, I've heard you. Yes, climate change is a concern. It's not our only concern. Should we not care about these people? Should we not give them propane? Should we applaud their death from emphysema and respiratory diseases because they live in poverty?

I'm anti-poverty, pro-electricity, pro-fuel, pro-energy. Why? Because electricity, in particular, frees women and girls from the pump, the stove, and the wash tub. If we care about women and girls, we must get them away from washing clothes by hand, feeding the stove with wood and carrying dung on their heads to have a fire. That's the humanist instinct, and yet it's just ignored in this insane attachment to climate as the only issue.

Ed Coyne: Getting energy to the world is probably the number one goal. We talk about expanding the electric grid and all these things that need to happen. We also need to deal with that in our own country. I know you've talked about this in the past. Well, let's go to the basic blocking and tackling of electricity, not just storing it but moving it. With our current grid system in the U.S., what kind of shape is that in, and what needs to change, if anything?

Robert Bryce: This is a big question and a big issue for many entities around the country. It's one that, in watching Chris Wright and his confirmation hearing before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, kept coming up again and again. It was based on the reliability and expansion of the grid. We have to start from a certain spot, which is understanding how big the system is.

The larger something gets, the harder it is to change it. You won't see Google double its revenue in a year at this point. In a small company, you could double your revenue with one sale because of smaller numbers. Once a system, company, or something gets to be very large, it's hard to change it. It's hard to make an expansion that's significant in gross terms. Think of it this way. We now have an electric grid in the U.S. with 1.3 terawatts of generation capacity. That's 1.3 million megawatts or 1,300 gigawatts.

Think of it, "Oh, 1,300-gigawatt-scale nuclear reactors." It's hard even to imagine what that means, right? We're not just going to add another 1,300. We're not going to double the size of this in anything in the near term, nor are we going to be adding some massive amounts of new miles of wire to the system because it's hard to build that stuff. You need labor, bucket trucks, electricians and transformers.

You need these things to make these incremental changes to a system this big. While that's easy to talk about, it's hard to do. It's hard to do because of the supply chain issues. It's hard to do because of the skilled labor issues. All these things come together when it comes time to try and change this system that we call the grid. There's nothing simple, cheap, or easy about it.

Ed Coyne: I wanted to go back to nuclear just for a second.

Robert Bryce: Sure.

Ed Coyne: It is something that I think the younger generation is embracing, and they understand it. That's partly because tech said, "We need more electricity. We need 24/7 baseload. We're looking to nuclear as one of the solutions for data centers and so forth." Does that seem realistic, or is that aspirational? In your life's work of 30 years of doing this and stuff, you've seen the ebb and flow of nuclear over the years. Does it seem like we're on a permanent upswing now? Talk about that briefly, and then we'll close this out.

Robert Bryce: Sure. To your last question, I think it is different this time for a lot of reasons. Let's talk about the generational issue. I'm going to disagree a little bit with what you said about the younger generation now. They have a more positive view of nuclear power because of technology. Tech is a late joiner here. We've only seen big tech coming on in the last year or so, with Amazon saying, "We're going to embrace tech”, and Google and Microsoft with different announcements and press releases.

Good for them. I'm glad to have them join the party. I'm 64. My oldest kid is 31. This younger generation didn't grow up under the specter of the bomb. They have a different view on nuclear power and a different view on its urgency because of climate change. In their lifetimes, they have been more predisposed to believe in nuclear power and be pro-nuclear because they were concerned about climate change. That's perfectly valid.

I think there is a generational change. That's one that's very positive. You see even some of the younger leaders in the nuclear movement now, Matty Healy and Paris Ortiz-Wines, Emmet Penney, and Mark Nelson, to name a few, who are leading this new charge because of their belief, not just in the viability of nuclear but their concern for the climate. That's different. It's this generally, this nuclear renaissance, the comeback. It's not being led by people of my generation, the ones who are the face of this. That's very positive.

Add in Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the changes that means for energy security in Eastern and Western Europe. You see much more momentum now in Estonia, Romania, France, and numerous European countries, saying, "Ha, natural gas is $12, $13, $14 per million BTU. Nuclear makes sense for us." That's not the same economic here in the U.S., where gas is around $4. Different economics are helping drive this in Europe. Meanwhile, you've got China building more nuclear plants than any other country in the world.

Ed Coyne: Still building coal plants, as you said earlier.

Robert Bryce: They're building five times as many coal plants as nuclear plants, but that's a different discussion. I think it is different this time in terms of nuclear. The questions, of course, will be the same as I talked about with SMRs. What about the fuel? Well, there's no shortage of uranium. We're going to face some pinch points in fabrication and enrichment. That's something the Trump administration will have to deal with.

I think we've got a deadline here in the U.S. by 2027 under the bill that John Barrasso got passed that will eliminate Russia as a fuel supplier into the U.S. unless you get a special dispensation or something like that. Different parts of this fuel supply chain must be solved at once. It all depends on the mining, the enrichment, the fabrication, whether it's into TRISO[1] or HALEU[2] or whatever the final package goes into the reactor. Nothing about this again will be quick, cheap, or easy.

It will take deliberate effort, deliberate investment, and strong governmental support. That will be a problem here in the U.S. because Congress is fractured. The Democrats are reluctantly pro-nuclear. The Republicans are pro-nuclear, but this one guy said, "What do you need for nuclear to work in the U.S.?" Well, you need pro-nuclear legislators. The problem is that the Republicans are pro-nuclear and anti-government. The Democrats are anti-nuclear and pro-government.

You need pro-nuclear and pro-government legislators because it will take strong government backing regardless of whether gigawatt-scale or smaller. The government must be involved to ensure the fuel supply is secure. It will also play a role in lending and loan guarantees, among other things. It all matters. Again, I'm very hopeful. I think it is different this time. I've given you a long answer, but there's nothing simple about where we are about this.

Ed Coyne: Certainly not simple. I know you mentioned earlier your Substack. I'm assuming that's probably the best way for our listeners to follow you and stay up to speed on what you're doing.

Robert Bryce: Robertbryce.substack.com.

Ed Coyne: Yes, I was going to ask you. Please let us know what that is. Thank you for that. I always ask this because I'll miss ideas and questions. Is there anything else you were hoping to address or talk about today that I didn't mention? Is there anything you want to leave our listeners with that may be of interest?

Robert Bryce: Sure. I'm thinking a lot about this lately about just outlook. It's easy to be pessimistic today and look at things and say, "Oh, we're doomed." We live in an incredible time—just an amazing time of incredible change. I think about my late mother and the change she saw in her lifetime. My grandmother was born in a house with a cave underneath in the basement, a cave my great-grandfather dug when he homesteaded in the plains in Oklahoma in the 1890s.

Ed Coyne: Wow.

Robert Bryce: The change she saw in her lifetime. We live incredibly fortunate lives. What I would encourage people to do is know their math when it comes to these energy and power issues. Know your physics. Don't be afraid to say, "I'm pro-energy and pro-human." We need more people who are willing to say that. Nuclear is part of that, but it's broadly across the board. We need more energy so we can have more people thriving and contributing.

This Malthusianism and this anti-humanism that has been dominant in many parts of our society, unfortunately, I think, is the wrong way to go. I'll put it that way. I could put it in much stronger language. I encourage people who are listening to be pro-human. Be pro-energy. Don't be bashful about it. Say it proudly because we need more people to stand up and say, "Yes, climate change." Okay, climate change. Regardless of what you think about climate change, we will need more energy, period. How are we going to do it? Nuclear energy will be part of that, but gas, oil, and the rest are all important.

Ed Coyne: Now, I think that's a key. What you said about people in parts of the world cooking and just pure safety stuff. I have to be honest. I didn't even think or know about that. I think those kinds of things need to be talked about more. I appreciate you lending your comments today. Hopefully, our listeners will clue in on your Substack, continue to follow you, and watch your work. Thank you for taking the time today to join us on Sprott Radio.

Robert Bryce: It's my pleasure. Thank you, Ed.

Ed Coyne: Thank you. Once again, I'm Ed Coyne, and you're listening to Sprott Radio.

[1] TRISO fuel, which stands for TRi-structural ISOtropic particle fuel, is considered one of the most robust nuclear fuels available. Each TRISO particle consists of a uranium, carbon, and oxygen fuel kernel, encapsulated by three layers of carbon- and ceramic-based materials. These layers prevent the release of radioactive fission products, making the particles extremely resilient.

[2] HALEU stands for High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium. It is uranium enriched to between 5% and 20% in the isotope uranium-235 (U-235), which is the main fissile isotope that produces energy during a nuclear chain reaction. HALEU allows for smaller reactor designs that produce more power per unit of volume, optimizing fuel utilization and increasing efficiency.

Important Disclosure

This podcast is provided for information purposes only from sources believed to be reliable. However, Sprott does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Any opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This communication is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument.

Relative to other sectors, precious metals and natural resources investments have higher headline risk and are more sensitive to changes in economic data, political or regulatory events, and underlying commodity price fluctuations. Risks related to extraction, storage and liquidity should also be considered.

Gold and precious metals are referred to with terms of art like store of value, safe haven and safe asset. These terms should not be construed to guarantee any form of investment safety. While “safe” assets like gold, Treasuries, money market funds and cash generally do not carry a high risk of loss relative to other asset classes, any asset may lose value, which may involve the complete loss of invested principal. Furthermore, no asset class provides investment and/or wealth “protection”.

Any opinions and recommendations herein do not take into account individual client circumstances, objectives, or needs and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies. You must make your own independent decisions regarding any securities, financial instruments or strategies mentioned or related to the information herein.

While Sprott believes the use of any forward-looking language (e.g, expect, anticipate, continue, estimate, may, will, project, should, believe, plans, intends, and similar expressions) to be reasonable in the context above, the language should not be construed to guarantee future results, performance, or investment outcomes.

This communication may not be redistributed or retransmitted, in whole or in part, or in any form or manner, without the express written consent of Sprott. Any unauthorized use or disclosure is prohibited. Receipt and review of this information constitute your agreement not to redistribute or retransmit the contents and information contained in this communication without first obtaining express permission from an authorized officer of Sprott.

©Copyright 2025 Sprott All rights reserved