Sprott Radio Podcast

Sprott Debates #2 - David Rosenberg & Don Luskin

Will the Fed continue to cut? Is there still a possibility of a recession? What’s the trajectory for gold? To tackle these timely questions David Rosenberg and Don Luskin join Ed Coyne and John Hathaway for round two of our Sprott Debate series.

Podcast Transcript

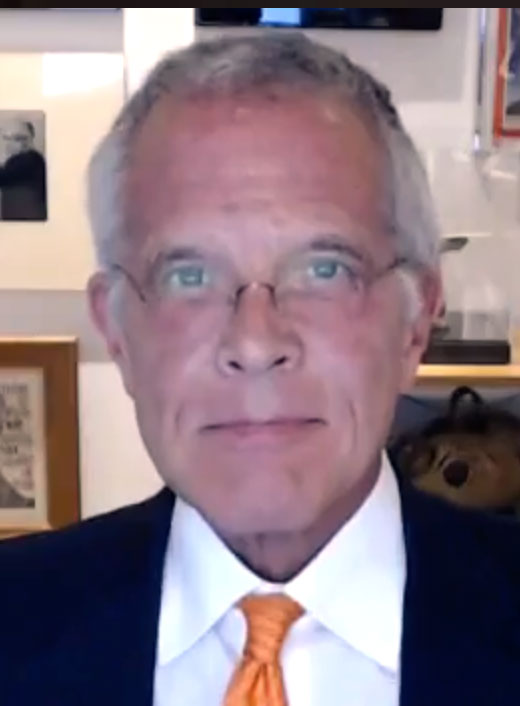

Ed Coyne: Hello and welcome to Sprott Radio. I'm your host, Ed Coyne, Senior Managing Partner at Sprott Asset Management. In April of this year, we hosted our first in what's becoming a series of debates. Once again, we have John Hathaway, Managing Partner and Senior Portfolio Manager at Sprott Asset Management, serving as today's moderator. Our two guests are Don Luskin, Investment Strategist and Founder of TrendMacro, which focuses on macroeconomic analysis and forecasting. We also have David Rosenberg, Founder and President at Rosenberg Research, which focuses on macro and market insights. I'd like to turn it over to John Hathaway to kick off today's conversation. John?

John Hathaway: Ed, thank you very much, and welcome to David and Don. I look forward to your comments over the next 45 minutes. There's a lot to cover. I would say the big three topics are inflation, recession, and the Fed. I think there are other things we could talk about, and geopolitics could certainly fit into it, but I would say let's start with inflation. David and Don, I think you both feel that inflation is a thing of the past. I would ask both of you for your arguments on why inflation has been vanquished and whether the Fed acted prematurely, and may be triggering a new round of inflation with a return to easier monetary policies.

Don Luskin: I have the old-fashioned belief that Milton Friedman won the Nobel Prize for in 1976 and that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon. There are different ways that the money supply can be increased or decreased by various government entities responsible for it, primarily the Fed, but from time to time, including the most recent time, the U.S. Congress, but you can never really say that inflation has confidently gone away any more than you could say dandruff has gone away. You can make it go away for a while by treating it, but you always have to be vigilant. It might come back.

I take the spirit of your question to be, has the multi-generation bump in inflation that we experienced in 2021 and 2022, which now seems to have returned to the Fed's target, reliably gone away? I think the answer is yes. I don't believe they caused inflation or are responsible for having cured inflation, at least for a while. I believe that what caused the inflation was simple. Over about 12 months, the money supply went up by $6 trillion because there were three back-to-back-to-back stimulus bills that two Congresses and two presidents voted on.

It was a bipartisan spending fiasco that injected cash into M2 and people's savings accounts, money market funds, and checking accounts. The idea was to stimulate the economy to escape the disaster of the COVID lockdown, which should have never happened in the first place. We had to buy our way out of it, and that caused inflation because, on a year-over-year basis, the money supply rose by 27%. That beats the previous record by about a factor of two, and that record we saw back in the '70s. That's where we got the inflation.

What's given us the disinflation is they stopped passing these stimulus bills. Under President Biden, there have been some spending bills, but they haven't been $6 trillion. They've been a trillion apiece, two of them, and one of them much less than that. They staged their payouts over a decade, so of course inflation will roll over. I think inflation would have rolled over just about the same even if the Fed kept interest rates at zero.

There's no reason to do that, so I'm glad they didn't, but I don't think the Fed caused this inflation or cured it. Another amazing thing is they also didn't cause a recession. David and I may disagree on whether we're going to be able to look back three or six months from now and still say that, but it seems like, so far, they haven't. That's miraculous. What that's telling us is that when you can take rates from zero to five and three-eighths in, say, call it 24 months and not cause a recession when they said they wanted to, that's telling you something.

That tells you that regardless of what the near future may bring in terms of recession risk looking forward, that means that at least over the last three or four years, while the Fed has tightened, we've had an amazingly robust, almost kind of a post-war boom economy coming out of what I like to think of as World War III, which was the war that all humanity waged together against the virus and won. The Fed was unable to cause a recession, so the Fed must be concluding that the natural rate, the neutral rate of interest, is much higher now than it was in those awful years of secular stagnation after the Great Financial Crisis.

After the Great Financial Crisis, the 10-year yield was, on average, 2.5%. About a year ago, we saw the 10-year yield slightly above 5%. We haven't seen that since before Lehman. Now, 5% isn't all that high of a 10-year yield. If you think that's abnormal or high, you're young. There's nothing special about that rate except that it didn't cause a recession. Remember, the Fed panicked in 2019 after they'd raised the funds rate to two and three-eighths. That used to be seen as a high interest rate. We've been at much higher interest rates for a long time, and it hasn't caused a recession.

The Fed is not as tight as it thought. That means when it starts cutting rates, it's not going to have to cut them as deeply as the market now expects, and I think even as the Fed now expects, and if the Fed does cut too quickly, then there is a risk that there'll be an inflationary resurgence. Nobody knows where the neutral rate is. I don't. Jay Powell doesn't. Dave Rosenberg doesn't, but I don't know; I'll bet nobody would disagree that it's something south of four and seven-eighths where the funds rate is.

The markets think it's about two and seven-eighths, 3%. I don't. I think it's probably in the fours. I don't think the Fed's going to venture below that. If it does, then inflation's going to come back. It's as simple as that. I'm going to say one more thing. After we stopped passing all those stimulus bills, the money supply contracted on a year-over-year basis for the first time in official history, beginning in 1959.

Historians tell us it contracted during the Great Depression, and I believe them, but the official data starts in 1959. At worst, about a year and a half, two years ago, we had a contraction in M2 of 4%. Having it be a contraction at all on a year-over-year basis is completely unprecedented. Yet, all that's happened with inflation is we've gotten approximately back to the Fed's target. We didn't have deflation. We had a minus sign in money supply growth but never got a minus sign in prices.

If you can have the only time in history when you have a contracting money supply on a year-over-year basis and not have deflation show up after you wait for it a year and a half, say, and not have that show up in CPI on a year-over-year basis with a minus sign in front of it, well, that tells you that in the future, we can probably tolerate in this economy less money supply growth than we could have, say, 5, 10, or 20 years ago, without causing inflation. We've brushed the dandruff off our shoulders. It could easily come back if the Fed doesn't recognize we're in a new world.

John Hathaway: David, Don seems comfortable with the idea that we have not experienced a recession and will not. I'd like to hear your view on that.

David Rosenberg: I want to remind everybody that when Donald Trump was elected in 2016, everybody thought we would have an inflationary cycle. Despite the fact that he raised tariffs and built this immigration wall against labor, and then we closed 2019 before COVID with GDP growth running between 2% and 3%, and we had the unemployment rate at 3.5%, where was headline and core inflation back then? It was roughly 2%.

Of course, we had COVID, an initial deflationary shock. Then, it turned into a massive inflationary shock because of all the demand stimulus from the government that bumped against the deterioration we experienced and the global supply chain structure. Next thing you know, we went from almost 0% inflation in the summer of 2022 to 9%. That was corrected because, as Don accurately said, we have not seen recurring fiscal stimulus.

There's still stimulus in the system from the lags from a couple of years ago, but that impetus to demand is gone, and the supply chains, by and large, have been restored. We'll see what happens in the Middle East and with this dockworkers strike, which I think will be just short-term in nature. The supply side has experienced a significant thaw on the product side, and at the same time, if you remember, everybody was talking about the great retirement theme and that women would never come back into the workforce because of childcare costs and lingering fears over pandemics. Here, the prime working-age adult participation rate is at a two-decade high.

You've had a tremendous thaw in the product market on the supply side, a tremendous thaw on the labor market on the supply side, bumping against the fact that stimulus from fiscal policy has subsided dramatically. My approach towards inflation is always about supply and demand. That's why you want to talk to an economist in any event. You get the price of anything, including the aggregate price level and its direction, by identifying the shape and the movements in aggregate supply and demand.

When I talk about the fact that we've had this expansion in the labor force, the pool of available labor in the U.S. now is running about 10% year-over-year. We've got a fresh number on Friday, but we've got productivity growth running very close to a 4% annual rate, and this is without the benefits of AI kicking in yet. This is all productivity that stemmed from companies having to digitize and automate during COVID. Many old economy sectors, even retail, that never had productivity growth realized that we either become Amazon or fail.

Productivity growth of almost 4%, John. Productivity is an inherent inflation killer, and this is before the benefits, whatever they will be from the AI wave that lies ahead in the future. You've got this tremendous boost to the supply side of the economy happening when demand growth, while still positive, is cooling off. People like to point to GDP growth of 3%, but with all due respect, a third of that growth was inventories. Underlying demand in the U.S. is running a bit below 2% at a time when the supply side of the economy is expanding at a 4% annual rate.

You see what's happening here, John, is that we are building up excess capacity, excess supply in the U.S. labor market, as the trend and unemployment rate tell you. Of course, the industry capitalization rate is trending lower. We're building up more excess supply in the economy, and this is still early days, so there's not a snowball's chance in hell you can look at the supply-demand curves right now and lead yourself to an inflationary conclusion.

As far as the call on the recession, I understand the recession hasn't come yet, but I come from a framework where the U.S. is an intensely credit-driven and interest-rate-driven economy. An interest rate cycle, the market cycle, and the economic cycle are centrifugal forces. They're like sine waves over time that move with each other, but they don't overlap necessarily with each other. There are long lags between interest rates and the real economy.

I'll take you back because we'd be having the same conversation, probably in the summer of 2007, and Don would be saying, "Where's this recession already?" and John, I'm sure you'd be saying the same thing. Remember, the Fed started raising rates in June of 2004, and the recession that nobody saw began in December 2007. It takes time for interest rates to work in both directions, and it's not unusual to see those lags between 24 and 30 months; that's where we are right now, and they work in both directions.

Historically, after the Fed cuts rates, if we go into recession, the rate cuts will generate an economic recovery, but that's usually roughly 18 months after the first rate cut. I would suggest let's not be so impatient. Let's not be tempestuous, and please, let's not ignore the business cycle. The business cycle has not been repealed. It's just that the lags are often very long. Then, what happens invariably is that people throw in the towel because the recession hasn't arrived yet.

It'd be very unusual after this interest rate shock that we've endured and continue to endure; what the Fed did at the last meeting was a speck of dust relative to the damage it has done from 2022 to 2023. I understand people don't believe there will be a recession because it hasn't happened yet, but I'm not fussed. Remember, the Fed started raising rates in 1988, and the recession didn't start till July 1990. Similar situation. Where's the recession? Give it time, and respect the lags between what the Fed does in time A and what the economy does in time Z. That's my point.

John Hathaway: I would point out that 80% of money managers believe we will have either no recession or a soft landing. It seems to me, and I don't want to inject too many of my thoughts into this, that if you read earnings reports and guidance from companies like FedEx and Dollar General, two things come to mind: the consumer is struggling, and business is slowing. What would be your thoughts about when our patience will be rewarded for those of us expecting to see a downturn?

David Rosenburg: The Fed has trained the markets to focus on coincident and lagging indicators. The leading indicators are already there. Most of them, not all. I think that the last man standing is always nonfarm payrolls. Once nonfarm payrolls decline, and I think when they decline in the first month, people will say, "Oh, it's just one month. It's not a pattern," and so on because nobody wants to call for a recession. Still, we'd have to wait for payroll employment to start declining.

Interestingly, the household survey has already shown employment to be declining, and the number of jobs in the household survey is down 66,000 over the past year and down more than one million for full-time workers. What's interesting is that companies are hoarding labor. They're shifting people from full-time to part-time and cutting hours, so they're rationalizing labor by not firing people because of the miserable experience of doing that in 2020 and 2021. Then you can't find them again.

The one thing that I'm noticing is that the hiring rate, as we already got the numbers from the JOLTS today, is like a hot knife through butter. It's down to where it was in the second quarter of 2020, the best leading indicator. The hiring rate leads the firing rate. I think that what has people confident there's no recession is that the labor market, in terms of the level of employment, hasn't started to contract yet. I think that as far as the markets pricing that in, and some markets have priced that in—ook where the treasury market is—the equity markets are in a different universe altogether, up until what China did on their liquidity measures. These weren't real measures to bolster the economy but to bolster investor sentiment. Commodity prices, oil, and base metals were in a significant downturn until this week. On the other hand, regarding the equity market, I think that when you talked about the Bank of America survey, you're talking about equity investors and equity investors always have a positive hat on.

Unless you run a short fund, every equity portfolio manager I've ever gotten to know in my 40 years in the business is always optimistic, so that doesn't mean a whole lot to me. For the markets to say, "We've seen the whites of the eyes of the economy," they're going to have to see the lagging indicator of employment, and I'm talking about payrolls starting to show minus signs in front of it.

John Hathaway: Could you clarify the hiring rate in the JOLTS report? Has that been declining sharply? You said a knife through hot butter.

David Rosenburg: Yes, the hiring rate has gone below 2%. If you see the chart of the hiring rate alone, you'd wonder where this rosy-posy Goldilocks soft landing view is coming from. The hiring rate is in a fundamental bear market. Boy, I'd love to show that chart to a technical analyst. It's down to its slowest level since the economy was in the pandemic lockdown recession in the spring of 2020.

The firing rate holds the glue together, which we see in the jobless claims data. The firing rate has remained inordinately low because the business sector is like the little boy with the finger in the dike. They've not been laying off people. The household survey is much richer in terms of the information it provides. To be sure, it's a lower sample size and a higher error term. The payroll report that everybody trades off of gives industry information, but it doesn't give you any more information about the quality of jobs being created.

The jobs being created are part-time and self-employed, and there is an absolute boom in the number of people taking on more than one job, multiple job holders. If you look at the jobs of multiple job holders in the U.S., people are taking on more than one job. By the way, this isn't the gig economy, which has been around for a while. This happened in the past several months or the past year. People are so stretched that they're taking on more than one job. This is a classic contracyclical indicator. You see, the payroll survey doesn't tell you that. It's in the household survey.

The bottom line here is that companies are hoarding labor. At the same time, they are dramatically reducing their hiring rate, and I don't know what month this will happen, but at some point, the hiring rate will overtake the firing rate. Then we're going to get nonfarm payrolls printing negative. You're going to get all the shills and mountebanks telling you to ignore that; it's just temporary, but that's when the ball is going to be rolling towards the recession that everybody thinks isn't going to happen, and that's when the Fed is going to be becoming very aggressive on its rate cuts.

John Hathaway: Thank you. Don, I'm sure you've been saving up a lot of commentary on this. Let's hear your response.

Don Luskin: First, I agree that there's a sufficient statistic that will tell us when this long-awaited train of recession finally reaches the station we've been waiting at so patiently is indeed when you start seeing payrolls rollover. I say that David, all your arguments are very good, but I say it because isn't it funny how, in conversations like this, we all throw around the word recession as though we all know what each other means by it? Right? Some people think it means two-quarters of negative GDP. If that's your standard, we had that in Q1 and Q2 of 2022, and the NBER didn't call that a recession. Why? Because payrolls rose every month during those six months.

The NBER does not publish a formal definition of recession. They're kind of like the Fed. They say we'll know when we see it. We look at the totality of the data. Looking back at the history of when they declared the end of a business cycle expansion at the onset of a recession, it corresponds essentially to the first time you see a negative payroll print. We can agree on whatever definition of recession we wish for this conversation; it's up to us, but if we want to use the official definition, then the business cycle is the labor cycle, so, fair enough, let's wait until we see that.

While you were talking about the household survey, I was looking up the numbers. I don't know if you've made, David, the appropriate adjustments for the annual changes in population controls. If you do that, it's not quite the long-term downright decline you're talking about. We're not at all-time highs. I'm not saying it's the most robust picture, but what I do every month on the first Friday when the jobs report comes out is I look at those two surveys, the payroll survey and the household survey, and I say, okay, these are the headlines. This is what everybody's looking at. Let's fact-check them.

There are all kinds of other good labor market indicators that have different degrees of precision and different degrees of objectiveness. You mentioned claims, which are good. There are a couple of Challenger layoffs, the employment component in ISM, manufacturing and non-manufacturing, and ADP. I've built just a simple Excel-based regression model that goes back and merges all those labor market statistics that aren't the ones that come from the BLS every first Friday. They show something more optimistic than the household survey and less optimistic than the payroll survey.

I believe in multimodal research; if you have more than one source, you should try to look at them all and put them together synergistically. I think you're more likely to come up with the right answer that way. If you had done that, you wouldn't have been surprised by that warning about what the annual benchmarking process will do to payrolls. You know what that is, David? They will take 818,000 jobs off when the jobs report comes out for January next year. What do you know? My model would've come up with literally the same number. That's how much payrolls have been off.

If you ask me, we're looking at a labor market, and I hate to say it, as Jay Powell says, it's a maximum employment market. Now, I suppose you're on a high, narrow pedestal and riding for a fall just because you're at maximum employment. You can't fall out of the basement window. We're not in the basement. We're in the penthouse in the labor market. I get that, but just because you're in the penthouse doesn't mean you're going to throw yourself out the window.

Of course, the hire rate is slowing. We're at maximum employment, so that is not inherently a warning unless I thought there was some huge pool of people desperately seeking employment who couldn't get it, and that's not the case. The labor force participation rate is back to the pre-COVID levels. I believe you made that point yourself, David. I don't disagree with your facts in particular. I don't see how those are recession indicators. You didn't quite say they were. I respect that your recession argument is based on long and variable lags. That's a perfectly reasonable way to look at it. That would be to quote Milton Friedman.

I want to say one thing about that: you and I, David, earn our living by being like economic historians. Both of us are very facile with the data. We both try to get it to tell us the truth. I think we've probably both been known to torture it until it confesses, but at least it's objective data. One of the things when you play that game is that you have to assume that the four most expensive words on Wall Street are: this time is different.

There is a book called This Time Is Different. That's a wonderful book. I treasure that book. Its title is sarcastic because it says no, and this time is not different. It is never different. When you go into a credit cycle, it's never different. There's going to be a consequence. I accept that, except I think this time is different. I think this time is different because of the experience we all lived through together in 2020 when all the world's authorities decided within weeks that we had to completely shut down the global economy, which induced a global depression.

In the U.S., where I am familiar with the numbers, we got to a 15% unemployment rate within a month. We went from 3.5% to 15% in one or two months. We lost more than 10% of real GDP. That's two and a half times what we lost in the six quarters of the Great Recession, where we only lost something like 3.8%, which was a great recession. When you lose 10% in just two months, there's no other word for that but depression. To see those unemployment rates and that loss in output, you truly have to go back to the early '30s.

The big difference between what we lived through in 2020 and what our grandparents endured in The Great Depression is they had to go through a whole decade of it, and they didn't get out of it until World War II presented the greatest public works effort in the history of the world. We got out of this in three months. We had a standard V-shaped recovery like you would normally have from the most shallow recession from a depression.

There has never been, I will put to you, in human history an economic fluctuation that negative, that deep, and that took such a short period of time. When you come out of that, all of our trusty economic, historical knowledge that we've used to guide ourselves through all our long careers and that lead to maxims like don't ever say this time is different. We have to throw out things like the index of leading indicators and the yield curve and all these things that have been calibrated over many loving decades to work in a world that isn't the world we're in. This is a unique moment in economic history for economists, strategists, and investors, where you need to wait and see the whites of their eyes.

John Hathaway: If I can replay that, Don, you think we're in a completely different world where we need to toss out these traditional precursors or warnings of recession, yield curve inversion, that sort of thing. To put it from David's point of view, there's still time for these lags to work, and we'll have to wait and see. I guess my only observation would be that the markets are pretty much on your side, Don, in terms of not expecting a recession, a lot of trust in the Fed, and if David turns out to be right, there's going to be a lot of upset in the markets. We could talk about this forever, but we have limited time.

Don, I listened to a webcast that you hosted. It was an expert,I think he was at the Manhattan Institute, talking about the fiscal projections under both a Harris and a Trump administration. I was frankly horrified by the projection. I think the takeaway for me was that under either administration, we would, in 10 years, be talking about $4 trillion deficits as a matter of routine. I'm bringing this up so we can shift to get both of your views on the issue, which, for me, has been constantly a concern, and that is what appears to be the intractable fiscal issues that the U.S. faces. I would like to understand whether you are concerned about the lack of willingness to address fiscal issues.

David Rosenburg: I guess I would say that I'm concerned, but I think we could all say we were concerned back in 2016 when Donald Trump added trillions of dollars. I mean, we were on the wrong side of the Laffer curve. The corporate tax cuts and the income tax cuts never paid for themselves, the tariffs never paid for themselves, and the debt ran up under Joe Biden as much as it did under Donald Trump, even adjusted for what happened with COVID. Here you have Don on, and you, John, saying the stock market is just ratifying Don's view; the stock market is a wonderful place. It's been a wonderful place for years with the fiscal deficit ramping up.

The dollar is weak, but has the dollar collapsed? After we've added on all this debt, what apple cart has been upset by it? We can sit here and talk about deficits and debts, deficits and debts, and I guess I don't know what you would've done eight years ago talking about the same thing. I got a couple of points on this. The first is that when you talk about the bond market, fiscal policy is not the only thing that goes into your equation when forecasting bond yields. You would have to, therefore, answer how it is that since last October, the national debt has gone up $1.4 trillion, and the 10-year treasury yield's gone down 125 basis points.

John, how's that even possible if you're so concerned about deficits and debts that will cause the treasury market to implode? It's not as if the Fed is doing QE, so what's going on? What's going on is that other things matter for bond yields, like inflation, inflation expectations, and Fed policy. As I said before, the interaction between aggregate demand and aggregate supply remains to be seen. You could have a fiscal policy that boosts both the supply side and the demand side.

I think Donald Trump's policies will do both because cutting top marginal rates in the corporate sector should unleash more capital formation, which is disinflationary as a static standalone event. He's pro-deregulation, which leads to lower business costs, which is disinflationary. Then we have the situation with tariffs if he goes ahead with them, but that's not a sustained source of inflation. That is a price level shift. I think Kamala Harris's policies are more traditionally Keynesian in nature, and her policies demand relative to the supply side.

I think, and this is where I'm different from the consensus, that her policies will be more inflationary, even accounting for the tariffs, which was, I said, he's not going to raise tariffs 100% every year. It's going to be a huge shock, that's for sure, but it's not a primary sustained source of inflation. It's not just deficits and debts; it's also the nature of fiscal policy and how it influences inflation and inflation expectations.

If you're going to say to me, John, I got a framework here that both candidates' fiscal policies will be very harmful to inflation expectations, it will place the Fed in a box, I'll say, okay. That's negative for my interest rate call, but it's much more complicated. I think that look, yes, it's like Don and I agree, when employment starts to decline, and for the markets, there's only one number that matters: nonfarm payrolls. At the same time, you know you're in a fiscal crisis when you have a failed auction or if you have some destabilizing plunge in the US dollar.

You and I go to that conference in Vale. How many years in a row have you heard from people talking about a cataclysmic plunge in the US dollar and that all these BRIC countries are ganging up against the U.S. because of the fiscal policy and, of course, freezing the Russian assets? Has that even happened yet? The one thing I will say is when interest costs-- and I only say this because we got the Canada experience of a near-failed auction in a crisis back in the early '90s when interest expense starts to drain more than the 30% of the revenue base, you're in deep doo-doo. We're still more than ten percentage points away from that, but we're heading in the wrong direction.

If that's the point where the risk of a real serious fiscal crisis, it's not about the debt, it's not about the deficits, it's about basically what a corporate CFO would say, "What's your interest coverage ratio?" That's when the rubber is going to meet the road. Yes, I'm concerned, but in terms of the impact and interest rates, it is complicated, more complicated than to say, well, deficits and debts, and the bond market will blow up because you'd have to answer why it hasn't happened already.

Bond yields didn't go up in 2022 and 2023 because of fiscal policy and debts. They went up because we had inflation, and the Fed went nuts in raising the cost of carry. That was just a story for the bond market. It wasn't about deficits and debts insofar as the fiscal policy stimulated aggregate demand at exactly the wrong time and created inflation; that's a different story altogether. But that's the story you'd have to have to turn the deficit debts into a story of rising interest rates, which has to somehow come down to what it does to inflation.

John Hathaway: I guess my only observation here is that the strength of the bond market could be discounting a recession. Indeed, that would be one explanation.

David Rosenburg: John, you just said that the markets favored Don's forecast, the Goldilocks economy. Then you're saying that the bond market is saying one thing, and the stock market is saying another. Is that what you're saying right now?

John Hathaway: Yes, I think that's right.

David Rosenburg: Then I pose a question: In your history, which market gets it right more, the bond market or the stock market?

John Hathaway: Bond market.

David Rosenburg: Case closed.

Don Luskin: Bingo. Let me interject on that point and say that compared to where we were a year ago when, for a brief shining moment, we had a 5.01 10-year yield. Now it's what, 3.72. I understand that higher 10-year yields, among other things, are correlated with higher growth expectations. Maybe we have lower growth expectations at this point at 3.72 than we did at 5.01, fine, but 3.72 is not a recessionary number.

There were very few moments in the 15 years after the Great Financial Crisis when we got as high as 3.72. There are people on Wall Street whose whole careers have thought that 3.72 was a high rate. Do you want to know what a recession number is? Thirty-one basis points on the 10-year March 7, 2020. Sixty-one basis points on the 30-year March 7, 2020. If this is a recession forecast in the bond market, it's mild.

John Hathaway: I think what we all want to know about in Sprott land or what we would observe is that the strength of the gold price may be discounting a lot of things. David, you mentioned de-dollarization, and I think you dismissed it as an issue.

David Rosenburg: Only for the impact on interest rates.

John Hathaway: It may be concerns about possibly a premature rate cut in a strong economy, which is Don's view is we're not going to have a recession, and maybe there was a reaction. There's geopolitics. I don't know how we factor that into any of this discussion except to say it's there and probably just imponderable. For me, the strength in the gold price may be an advance warning that maybe it's not a sovereign debt crisis tomorrow.

Maybe a recession will prevent that because money will flow into bonds as a safe haven. Still, I think a lot of markets look ahead on a much longer-term basis, and we've seen the gold price go up 70% over the last five years very quietly without a lot of Western participation. I would be curious to hear from either of you if you have any thoughts on that particular subject, which is near and dear to my heart.

Don Rosenburg: Yes, I'll just kick it off and just say that the performance of gold, especially in the last year to year and a half, has been especially amazing because it's done it in the face of a background economic scenario that is normally adverse to gold, which is we have gone from many years of negative real rates to pretty strong positive real rates, and we got there in a hurry, pretty amazing that didn't kill gold.

It normally does, and for gold to have just gradually made this assault on new all-time highs, just sneak it up there a little bit every day while that was going on—gold's even stronger than it looks if it can do it versus that. That's another case throughout the playbook; yes, this time, it's different. John, I would like to give you an idea you might want to use in the future. I know it's a tradition among gold investors to think of gold as an insurance policy against catastrophe, and I don't dispute that. I have a lot of physical gold, but gold is also a thing you need to increase prosperity.

If you get a nation like China, they will need more gold in their central bank than they ever thought. The Chinese central bank is so ridiculously under-golded compared to all its peers. That alone will keep gold trudging to new highs, and that will be all the more so when the world economy grows and when China grows because as the world economy grows, you need more gold to be the collateral for the credit of that growing world economy. It's like if you bulk up, work out, get bigger muscles, you’re going to need a bigger jacket.

John Hathaway: I think that's right. Certainly, it's a play on emerging markets. It's a play on rising prosperity in underdeveloped nations. All of that. It's just interesting that, yes, it has broken all the rules. Real interest rates are positive. That was supposed to be bad. People come to gold for many different reasons. What I think is very interesting is that it's done it without any participation from people in the United States or Europe who can't wait to sell the gold they have. There's some mystery to it. Lots of people think they have a reason for it.

Your explanation is a fair-weather, positive way of looking at it. It isn't necessarily catastrophic the way traditionally you hear from people in the gold camp. I don't disagree with that. I think it's good to have a fair-weather explanation, and that may well be it. It could be just that. Anyway, I would like to ask either of you if you have any closing comments. It's been a great discussion. Thank you both for your participation. I would look forward to another one, especially when the train comes into the station on nonfarm payrolls. I don't trust a lot of this data, but it does move markets, and that's what you all have to work with. Anyway, any concluding comments from either of you?

Don Luskin: I want to thank you, John, Ed, and David Rosenberg, to whom I've tracked your career the whole time. I wasn't always an economic strategist. I had to learn this business, and one way I learned it was by imitating you. I admire you very much, and it's nice to finally get to meet you.

David Rosenburg: The feeling's mutual. I'll finish off, John. I didn't get a chance to talk about gold along with treasuries, and it's probably a more accurate call than treasuries over the last several years. It's been my highest conviction call for a whole bunch of reasons. I don't have a price target because having one in something that doesn't deliver a cash flow stream is hard. I don't know where gold is going. I know it has several tailwinds, and when the tailwinds subside or turn to headwinds, I'll change my forecast, whether that's 3,000, 4,000 or 5,000. I will warn you guys and the viewers that the day that gold hits the peak will be when I change my name from Rosenberg to Goldberg.

Don Luskin: Beautiful.

David Rosenburg: You heard it here first.

Don Luskin: That's so beautiful.

John Hathaway: That's a great note to end on. Thanks, everybody.

Ed Coyne: Thank you, John, for moderating this. We hope to do one of these about every six months. It seems like six months is just enough time for things to change for better or worse, so please keep your invites open. We'd love to see you guys back on. I would also say for our listeners who'd like to learn more about our guests today, both Don and David, I encourage you to look them up on LinkedIn. They both have tremendous followings there, but I encourage you to check out their websites. Don's website at TrendMacro is trendmacro.com.

I encourage you to look at what Don's working on over there. The same goes for David Rosenberg at Rosenberg Research. Surprisingly, his email is also rosenbergresearch.com. I encourage you to look them up on LinkedIn and check out their website to see what they're up to and what they're thinking about. John, as always, thank you for moderating. You do a tremendous job with that. Hopefully, we all learned something today. Once again, thank you for listening to Sprott Radio.

Important Disclosure

This podcast is provided for information purposes only from sources believed to be reliable. However, Sprott does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Any opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This communication is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument.

Relative to other sectors, precious metals and natural resources investments have higher headline risk and are more sensitive to changes in economic data, political or regulatory events, and underlying commodity price fluctuations. Risks related to extraction, storage and liquidity should also be considered.

Gold and precious metals are referred to with terms of art like store of value, safe haven and safe asset. These terms should not be construed to guarantee any form of investment safety. While “safe” assets like gold, Treasuries, money market funds and cash generally do not carry a high risk of loss relative to other asset classes, any asset may lose value, which may involve the complete loss of invested principal. Furthermore, no asset class provides investment and/or wealth “protection”.

Any opinions and recommendations herein do not take into account individual client circumstances, objectives, or needs and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies. You must make your own independent decisions regarding any securities, financial instruments or strategies mentioned or related to the information herein.

While Sprott believes the use of any forward-looking language (e.g, expect, anticipate, continue, estimate, may, will, project, should, believe, plans, intends, and similar expressions) to be reasonable in the context above, the language should not be construed to guarantee future results, performance, or investment outcomes.

This communication may not be redistributed or retransmitted, in whole or in part, or in any form or manner, without the express written consent of Sprott. Any unauthorized use or disclosure is prohibited. Receipt and review of this information constitute your agreement not to redistribute or retransmit the contents and information contained in this communication without first obtaining express permission from an authorized officer of Sprott.

©Copyright 2025 Sprott All rights reserved